In late 2019, even as Riskline analysts were forecasting the potential for an outbreak of infectious disease in the coming year, I could not have predicted the manifold ways in which a novel pandemic would affect our lives, our work and the world more broadly. Even the most thorough assessment of a future pandemic could not have anticipated the consequences of the decisions made by so many governments, public health officials and individuals in this past year. If an analyst had predicted, for instance, that all business and leisure travel to Australia would be suspended for nine months (and counting), I would have demanded a rewrite, and secretly questioned their mental fitness.

And yet, we will try our hand again to envision what 2021 holds for the world, especially in the context of international travel.

But before we move into our 2021 forecast, let’s look at some of the key developments this year that our analysts got right in last year’s forecast.

The year saw major protests against racial discrimination and police brutality triggered by fatal police-involved shootings in the United States (US) that spurred the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and inspired similar demonstrations around the world, like the #EndSARS protests in Nigeria. There were also more frequent and severe natural disasters, such as the unprecedented wildfires in Australia and the US state of California. Meanwhile, we witnessed worsening China-US relations amid an ongoing trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic, which outgoing US President Donald Trump has blamed on China.

While we are not typically in the business of predicting the future, our analysts identified these developments in 2020 based on detailed analyses of ongoing and emerging trends. The deadly wildfires in Australia and California, for example, are a result of the ongoing effect of climate change which has led to more severe weather and volatile environmental conditions. Likewise, in the case of the BLM protests, we highlighted a rise in anti-system demonstrations as a key risk for 2020 due to growing popular discontent with governments in many countries, including the US. Additionally, while we did not predict a pandemic on the magnitude of COVID-19, we did indicate in our 2020 forecast that increasing migration and urbanisation coupled with strained health infrastructure and weak government response would see more outbreaks of infectious diseases.

But now let’s look ahead to 2021.

Early in the year we will bear witness to the schizophrenia of the American government (6) as a new administration enters the White House intent on erasing the works of its predecessor (much as the Trump administration did in 2017). This will be welcomed by some, dreaded by others but watched by all with scepticism, knowing that a new bout of mania could be just four years away.

While there is hope that some parts of the world will see the end of the pandemic next year, its effects will continue to be felt in 2021 and beyond. It’s not yet clear the extent of the damage to healthcare systems (2) or how long it will take them – and critically their workforce – to recover. Nor is it known the long-term effects on populations that were denied or postponed critical care or vaccinations for other deadly diseases. What’s also likely to be with us well into the future is the accompanying ‘infodemic’ – that virus of misinformation that often overwhelms sound public health messaging to infect whole populations.

Even as we come to grips with whatever might be our ‘new normal’ (7), we’re sure to see the return of widespread unrest driven by pre-2020 problems (3) – inequality, globalised capital and climate change – supercharged in a post-pandemic environment.

On the one hand, ongoing struggles for economic rights and environmental justice last seen in 2019 will resume, while others will emerge from those places hit hardest, epidemiologically and economically, by the coronavirus. On the other hand, promises to shield in-groups from the worst effects of recession and climate change will drive growing support for (mostly right-wing) populism.

With the unipolar world of the American empire looking increasingly like a relic of pre-pandemic days, regional players will jockey for power, with devastating results for the people who live there. In the wider Middle East, tensions between Iran and the emerging Israeli-Gulf alliance (4) will test the boundaries of what we consider the threshold for ‘war’, as both sides engage in cyberattack, misinformation, drone strikes and assassinations across the region. In East Africa, a dispute over political power in Ethiopia (5) could spiral into an insurgency or more violent conflict, pushing people to flee into neighbouring countries. Elsewhere, China is certain to flex its muscle in disputes over Hong Kong, Taiwan and terrorises in the South China Sea, while other conflicts – Syria, Yemen, northern Nigeria, Cameroon, Ukraine, et al – grind on with no end in sight.

Regional conflicts and other political violence, post-pandemic economic hopelessness in developing countries (8) and catastrophic environmental collapses (1): Taken together in 2021, will result in migration on a scale that could dwarf the ‘crisis’ of the 2010s. Absent an unprecedented global effort to ameliorate these ills that force people to leave their home, only state violence – taking the form of border walls, armed guards and naval patrols – will be capable of stopping these migrants.

But, let’s not be too pessimistic about 2021. It can’t be as bad as this year, right?

Happy New Year,

Adam Schrader

Director of Operations, Riskline

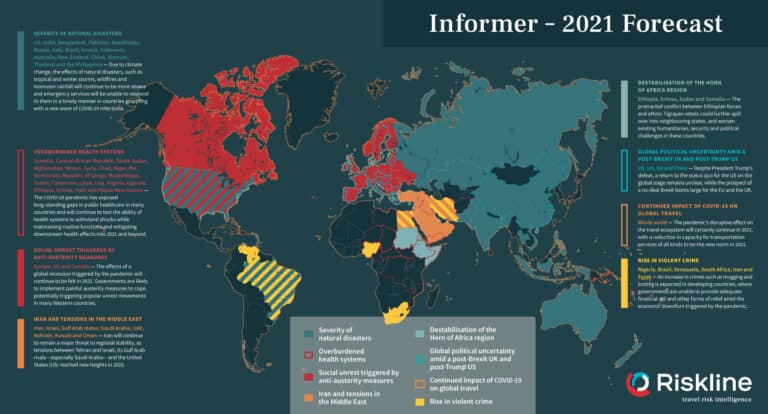

Top 8 Risks for 2021 (Download Map)

-

Severity of natural disasters

Due to climate change, the effects of natural disasters, such as tropical and winter storms, wildfires and monsoon rainfall in 2021 will continue to be more severe and emergency services personnel will be unable to respond to them in a timely manner in countries grappling with a new wave of COVID-19 infections. Slow and inadequate response by emergency services was witnessed in countries such as the United States, Bahamas, Barbados during hurricanes Laura and Delta between August and October 2020, where in some instances people avoided evacuation shelters due to the risk of spread of COVID-19 in close quarters.

In India, Bangladesh and the Philippines, when a series of cyclones hit between August and November 2020, emergency personnel were unable to evacuate residents or provide aid relief in many COVID-19 affected areas where they were not allowed to enter due to ongoing lockdowns. The trend will be similar when natural disasters hit countries in 2021, as emergency services are still understaffed and stretched thin and most resources have been allocated towards tackling the COVID-19 outbreak. Countries particularly at risk from natural disasters amid an outbreak during 2021 include the United States (US), Italy, Kazakhstan and Russia, during the winter-storm season (January-March); the US, Brazil, Greece and Indonesia (April-August), and Australia and New Zealand (January to April) during the wildfire season; and India, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Thailand, Philippines, China and Pakistan during the cyclone and monsoon seasons (May-November).

-

Overburdened health systems

The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed most health systems to their limits, exposing long-standing gaps in public health infrastructure and healthcare in many countries. A World Health Organisation (WHO) study from 105 countries indicates that some 90 percent of countries experienced disruptions to essential healthcare services, with low- and middle-income countries reporting the greatest difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic. Routine immunisation, diagnosis and treatment of non-communicable diseases, cancer and malaria, as well as family planning,contraception and treatment for mental health disorders have been the most affected.

Distressingly, emergency services also experienced disruptions in many countries. The pandemic will continue to test the ability of health systems to withstand shocks while maintaining routine functions and mitigating downstream health effects into 2021 and beyond, with Somalia, Central African Republic, South Sudan, Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria, Chad, Niger, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Sudan, Cameroon, Libya, Iraq, Nigeria, Uganda as well as Ethiopia, Eritrea, Haiti and Papua New Guinea among the countries with the weakest capacity to cope with the added burden of the pandemic. The cancellation or postponement of elective services and online patient consultations can also be expected to continue in many high-income countries.

-

Social unrest caused by anti-austerity measures/COVID-19 restrictions and vaccine deployment

In October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated that the global economy will shrink by approximately 4.4 percent in 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The effects of this recession will continue to be felt in 2021, even with the deployment of a vaccine. Lower tax receipts and ballooning public deficits are likely to force governments across the world to implement painful austerity measures, including cuts to social programmes and unemployment benefits. These actions carry with them the potential to trigger popular unrest led by activist organisations such as the Yellow Vest (Gilets Jaunes) movement in France and the

People’s Assembly Against Austerity in the United Kingdom (UK). Right-wing organisations in particular have increased their visibility and membership in the United States (US), Canada and Europe to protest COVID-19 restrictions, and will likely turn their attention to castigating vaccination campaigns and seeking the ouster of incumbents on all sides of the political spectrum. Disinformation to engage a wide coalition of low-information voters will proliferate and bring together loose coalitions of wildly divergent but “populist” factions. The speed with which life is able to return to a semblance of pre-2020 normalcy, particularly economically, will determine if these new coalitions have any staying power, but their anti-establishment, anti-state and anti-expert messaging has already transformed populist politics worldwide, particularly in the US and UK.

-

Iran and tensions in the Middle East

Tensions between Iran and Israel, its Gulf Arab rivals – especially Saudi Arabia – and the United States (US) reached new heights in 2020 with the assassination of Major General Qasem Soleimani in January and the country’s top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, in November. Iran has vowed to avenge both deaths, and its parliament approved a bill to suspend United Nations (UN) inspections of their nuclear program.

Meanwhile Israeli authorities have warned their own nuclear scientists and citizens to exercise increased caution in anticipation of possible attacks. A direct Iranian retaliation on US interests is unlikely but the government will continue to develop its nuclear capabilities and support allies and proxies in Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Iraq and Yemen. Iran’s ability to retaliate has been hampered by the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on an already ailing economy, and while a delayed response is expected in 2021, much will depend on the policy taken by President-elect Joe Biden towards Iran, Israel and the Gulf Arab states in 2021.

-

Destabilisation of the Horn of Africa region

On 28 November 2020, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed declared victory over the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) after federal forces captured the regional capital, Mekelle, following a near-month long conflict in the northern Tigray region. The conflict has exacerbated ethnic tensions within Ethiopia, spilled over into Eritrea – where TPLF forces have already fired rockets towards Asmara – and triggered the displacement of tens of thousands of Tigrayans across the Sudanese border. A protracted guerilla insurgency is increasingly likely in the months ahead after TPLF leaders pledged to continue fighting, and the prospect of disintegration and civil war looms as further fighting threatens to draw other regional states into the conflict. Finally, the wider Horn of Africa region is at an increased risk of destabilisation as the conflict could further spill over into neighbouring states, including Eritrea, Sudan and Somalia, and worsen existing humanitarian, security and political challenges in these countries.

-

Global political uncertainty amid a post-Brexit UK and post-Trump US

On 1 January 2021, the United Kingdom will have completed its year-long transition period following the country’s exit from the European Union (EU). However, the possibility of a no-deal Brexit, with implications for the economy and the Northern Ireland peace accords, continues to loom less than a month before the end of the transition period. Deal or no deal, the effects of Brexit will be just one of the several uncertainties to watch out for in 2021. While Democrat Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 United States presidential election generated optimism, he will have big challenges ahead in economic recovery and fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, as the number of new cases rose to a record high during the final months of the outgoing Trump administration.

Countries will have to consider whether the reversal of many of the Trump administration’s actions by a Biden administration will not simply be reversed should a Republican be elected in 2024, and plan accordingly.

France, with a presidential election approaching in 2022, will likely be the locus of US attention, more so than the UK. While a Biden administration will shore up alliances, countries will enter into regional blocs less dependent on the US in the event of further political turmoil. NATO will, in particular, have to address the Turkish elephant in the room as President Erdogan continues to insert himself in the domestic politics of other European member states and engage in military adventurism across the Middle East and Southern Caucasus. Additionally, Asia-Pacific partners such as Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and Australia, will demand greater attention to deal with an emboldened People’s Republic of China, which crushed dissent in Hong Kong and Xinjiang without concern for the international community’s response and is riding high on its “triumph” of containing the pandemic with lower loss of life than many other countries.

-

Continued impact of COVID-19 on global travel

Even as the global travel industry gradually recovers from the absolute standstill that it experienced through most of 2020, the pandemic’s disruptive and ever-changing effect on the travel ecosystem will certainly continue in 2021. The desire for countries to limit exposure to COVID-19 will put pressure on travellers to obtain mandatory documentation relating to insurance, testing, pre-approved accommodation and, eventually, vaccination, prior to travel, which imposes additional cost burdens on travellers.

Entry and exit restrictions imposed by governments or their assessment of the COVID-19 situation in a traveller’s country of origin change at short notice, further complicating global travel. Travellers in most countries should continue to expect measures such as health screening, quarantine and testing, socially distanced seating arrangements and contactless check-ins or transactions at airports, major public transport hubs, hotels and other facilities. Expect renewed lockdowns in high-risk areas and a reduction in capacity for transportation services of all kinds to be the new norm in 2021.

-

Rise in violent crime in developing countries

An increase in crimes, such as carjackings and burglaries, is expected in developing and semi-developed countries, whose governments are unable to provide adequate financial aid and other forms of relief amid the economic downturn triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The massive economic burden has already caused an increase in often deadly bandit and kidnapping-for-ransom attacks in Nigeria and armed break-ins in Iran and Mauritania in 2020, while in Brazil highly organised bank robberies have paralysed entire cities on more than one occasion.

As the pandemic rages on and the economic strain grows, criminal groups will likely have bigger recruitment pools, particularly among adolescents due to the closure of schools and universities and the lack of job opportunities. Due to this, incidents of violent crime will likely increase in countries that already experience high crime rates, such as Venezuela and South Africa. A rise in opportunistic crime, such as looting and muggings, may occur in countries such as Egypt, where organised groups do not normally operate.

Watch our webcast on this topic: