By Eeva Ruuska

How the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle works

During normal conditions in the Pacific ocean, trade winds move warm water along the equator from South America towards Asia. To replace that warm water, cold water rises from the depths. El Niño and La Niña are part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, and represent two opposing patterns that break these normal conditions.

During the cold phase, La Niña, normal trade wind conditions get stronger. During the hot phase, El Niño, trade winds weaken and warm water is pushed towards the west coast of the Americas. Periods of El Niño and La Niña typically last nine to 12 months, but can sometimes last for years. El Niño and La Niña events occur every two to seven years, on average.

Scientists forecast moderate or strong El Niño conditions by late northern hemisphere summer, while the intensity is set to peak at the end of this year. The phase will likely last until the northern hemispheric spring 2024, after which its impacts will recede. However, in past cycles, record-high temperatures have been recorded in the year after El Niño. Experts believe it will likely make 2024 the world’s hottest year on record.

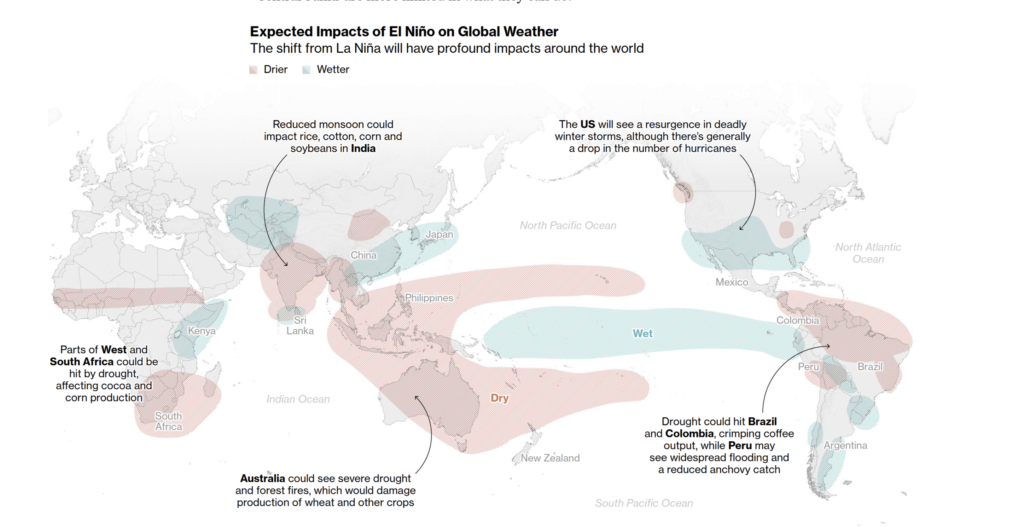

Weather impact around the world

El Niño will have significant implications for weather patterns across the globe.

El Niño often leads to drought conditions and wildfires across Australia and Indonesia, potentially weaker monsoon in India and stronger tropical storms across the Pacific.

Past El Niño phases have seen adverse weather patterns develop in northwest Europe and the UK, and hotter conditions across central Europe. El Niño typically strengthens drought conditions in western and southern Africa, and increases rainfall in eastern Africa.

During this period the northern US states and western Canada will be drier and warmer than usual, while southern US states will experience more rain and flooding, despite an expected drop in the number of hurricanes. There tends to be less snowfall in the northern US during the El Niño winters, but a higher risk of devastating winter storms in the central, southern and eastern US.

We can also expect drier conditions to develop in Brazil, Colombia and Central America. More extreme rainfall and flood damage is expected in the Southern Cone and western South America, where coastal El Niño conditions have been detected since March. Severe flooding from Cyclone Yaku left at least 84 people dead and 47,000 displaced in Peru and Ecuador. There were weeks of travel disruptions due to road damage from flooding and landslides, and record-high dengue fever outbreaks.

The potential Human and Economic Cost of El Niño

El Niño can have a large human and economic cost. The strong El Niño in 1997-98 cost over USD 5.7 trillion with around 23,000 deaths from storms and floods. The last strong event in 2016 caused an estimated USD 327 million losses in agricultural production. El Niño can have a devastating impact on the world economy, particularly on poorer Southern nations, due to related disasters. This may include catastrophic floods, food shortages due to crop-killing droughts, plummeting fish populations and an uptick in tropical diseases.

Travel and service disruptions can happen in areas of high rainfall and drought conditions. These disruptions may include:

- road, rail track and infrastructure damage from flooding and landslides

- power outages and supply chain disruptions due to sweltering temperatures, smog, evacuations and property damage due to wildfires

- flight disruptions due to snowstorms and overburdening of healthcare services due to heatwaves

- disease outbreaks such as cholera, typhoid and dengue fever

We’re yet to see how intense the coming El Niño will be. Yet with more extreme weather events and higher temperatures from climate change, this phase may well be the world’s costliest.